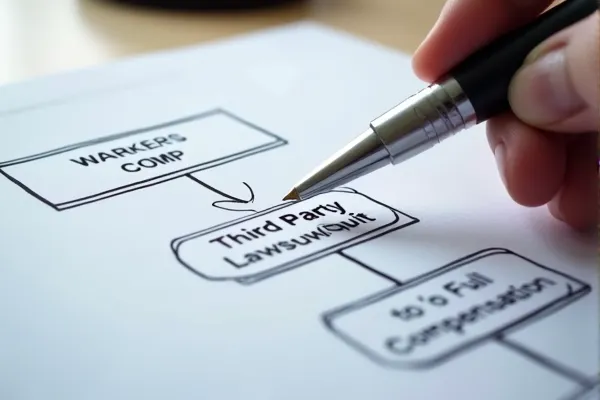

Under California Labor Code, you generally cannot sue your employer for a work injury; you are limited to Workers’ Comp. However, this rule does not apply to negligent “Third Parties.” If your injury was caused by a Subcontractor, Property Owner, or Equipment Manufacturer, you can file a personal injury lawsuit in addition to your Workers’ Comp claim. This allows you to recover “Pain and Suffering” damages that Workers’ Comp refuses to pay.

San Diego Third-Party Work Injury Lawyer | Suing Contractors & Vendors: what’s the fastest way to protect your case when someone other than your employer caused the injury?

Under the California legal framework, the most important rule is this: identify and preserve the “non-employer” liability path immediately—because contractors and vendors start controlling the narrative within days. While workers’ comp can pay basic benefits, it does not automatically hold a negligent third party financially accountable for your full losses. We apply the Morse Injury Law advantage to conduct a secondary investigation, looking for equipment defects or subcontractor negligence that standard reports often ignore. This groundwork allows us to bypass the limitations of the administrative system and seek maximum recovery in San Diego Superior Court venues. To understand how we separate third-party negligence from a standard jobsite accident, review our client resources guide.

How I build third-party work injury cases in San Diego (and why insurers try to bury the third-party angle)

Third-party work injury cases live and die on control: who owned the area, who supplied the equipment, who supervised the task, and who had the duty to make the condition safe. The baseline negligence duty is grounded in Civ. Code § 1714. Your right to sue a third party even when workers’ comp applies is anchored in Lab. Code § 3852.

Here’s a realistic San Diego scenario: a subcontractor leaves a trench plate unsecured near a walkway at a large commercial remodel, and a delivery vendor moves pallets through the same pinch point without a spotter. A worker goes down hard, fractures a hip, and the employer files workers’ comp—then everyone points at everyone else. Once the case is positioned for San Diego Superior Court, discovery forces contracts, safety plans, and site-control documents onto the table, and the “it’s just comp” story starts collapsing.

- We lock down who controlled the hazard (GC, sub, vendor, property owner, or all of them).

- We preserve the physical condition and equipment identifiers before they disappear.

- We treat workers’ comp lien issues as a math problem, not a reason to give up value.

Why California Law and San Diego Superior Court venue control leverage in contractor/vendor lawsuits

In San Diego, the defense playbook is predictable: “exclusive remedy,” “your employer was responsible,” “you weren’t following training,” and “we didn’t control the site.” That argument is designed to scare workers into staying inside the workers’ comp lane. The third-party lane is real, and it’s statutory: Lab. Code § 3852.

Venue matters because San Diego Superior Court is where you can force contracts, safety manuals, and incident documentation through discovery under CCP § 2017.010. Once those records come out, insurers lose the ability to hide behind vague “jobsite shared responsibility” language, and fault allocation becomes provable instead of hypothetical.

The “Immediate 5”: San Diego third-party work injury questions that decide whether contractors/vendors can be sued

1) Who was the negligent third party, and what did they control on the jobsite?

Third-party means “not your employer”: a general contractor, subcontractor, vendor, property owner, equipment lessor, or maintenance company. Under Civ. Code § 1714, liability tracks with duty and foreseeability, and control evidence comes from contracts, site rules, delivery schedules, and who had the authority to correct the hazard that injured you.

2) Is workers’ comp already open, and does that affect your right to sue contractors or vendors?

Workers’ comp being open does not erase the third-party claim. The right to pursue the negligent non-employer is expressly recognized in Lab. Code § 3852; the case management issue is the employer/insurer lien, which is handled through the lien allocation framework in Lab. Code § 3856 and settlement consent rules in Lab. Code § 3860.

3) What hard evidence exists beyond witness memories: contracts, daily reports, photos, equipment IDs, and incident logs?

In these cases, the defense will act like the hazard never existed or was “fixed immediately.” That’s why preservation matters, and why civil discovery is leverage. Requests for production under CCP § 2031.010 are how you force the paper trail: daily logs, subcontractor scopes, safety meeting rosters, inspection checklists, and delivery/vendor documentation.

4) Are you inside the lawsuit deadline, and does the timeline change when multiple contractors are involved?

Most San Diego injury claims operate under the two-year filing window in CCP § 335.1. Multi-defendant contractor cases feel “busy,” but the clock doesn’t pause while parties argue about responsibility, and late-added defendants create avoidable procedural fights that insurers love.

5) What changes once a third-party case is filed in San Diego Superior Court?

Filing converts “we’ll look into it” into mandatory disclosure and sworn testimony. Discovery scope is governed by CCP § 2017.010, depositions proceed under CCP § 2025.010, and you can force site-control documents and vendor records through CCP § 2031.010. That’s when “no control” defenses get tested against contracts and real jobsite rules.

Contractor and vendor cases are not about slogans. They’re about pinning fault to the party that actually created the risk, then forcing the documents that prove it.

- General contractor: site coordination, rules, and safety program implementation.

- Subcontractor: scope-of-work hazards and trade-specific control.

- Vendor/hauler: delivery practices, equipment movement, and on-site conduct.

Magnitude expansion: how San Diego third-party work injury claims are proven and valued

A) Evidence Evaluation in San Diego Cases

These cases aren’t won by “someone said.” They’re won by documents and physical proof that tie control and conduct to the injury.

- Incident documentation: supervisor notes, incident reports, and any jobsite log entries.

- Scene proof: photos/video, measurements, and equipment identifiers before changes occur.

- Treatment timeline consistency: the medical record must track mechanism of injury and progression.

B) Settlement vs Litigation Reality

Pre-suit, insurers posture: “It’s workers’ comp,” “we don’t have enough information,” and “your employer is responsible.” In San Diego Superior Court, that posture gets stress-tested through contracts, deposition testimony, and document production. The leverage shift is procedural, not emotional.

- Contract and scope documents reveal who had safety and corrective authority.

- Depositions lock witnesses into a jobsite-control story under oath.

- Workers’ comp lien issues are negotiated within statutory constraints, not left to guesswork.

C) San Diego-Specific Claim Wrinkles

San Diego job sites often involve layered contractors and fast-moving vendor traffic: commercial remodels, biotech campuses, downtown builds, and infrastructure work. The defense uses complexity to create doubt, then prices the claim down as “shared fault.” My job is to convert complexity into an allocation case backed by proof.

- Multiple tiers of subs create finger-pointing—contracts and daily logs cut through it.

- Vendor activity is often lightly documented—delivery records and equipment tracking matter.

- Insurer resistance commonly targets causation and control, not the injury itself.

Lived Experiences

Jeffrey

“My supervisor kept saying I couldn’t sue anyone because it happened at work. Richard explained the difference between workers’ comp and a third-party case, then proved the vendor controlled the equipment that failed. Once that was clear, the case stopped being ‘comp only.’”

Brooke

“The contractor’s insurance adjuster acted like the hazard didn’t exist. Richard forced the daily logs and the subcontractor scope documents, and the story changed fast. The outcome felt practical—medical bills handled, lien addressed, and the real responsible party finally paying attention.”

California Statutory Framework & Legal Authority

Attorney Advertising, Legal Disclosure & Authorship

ATTORNEY ADVERTISING.

This content is provided for general informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice.

Under the California Rules of Professional Conduct and applicable State Bar of California advertising regulations,

this material may be considered attorney advertising.

Viewing or reading this content does not create an attorney-client relationship.

Laws and procedures governing personal injury claims vary by jurisdiction and may change over time.

You should consult a qualified California personal injury attorney regarding your specific situation before taking any legal action.

Responsible Attorney:

Richard Morse, California Attorney (Bar No. 289241).

Morse Injury Law is a practice name and location used by Richard Peter Morse III, a California-licensed attorney.

About the Author & Legal Review Process

This article was prepared by the legal editorial team supporting Richard Peter Morse III,

with the goal of explaining California personal injury law and claims procedures in clear, accurate, and practical terms for injured individuals in San Diego and surrounding communities.

Legal Review:

This content was reviewed and approved by Richard Morse, a California-licensed attorney (Bar No. 289241),

who concentrates his practice on personal injury litigation and insurance claim disputes.

With more than 13 years of experience representing injury victims throughout California,

Mr. Morse focuses on serious personal injury matters including motor vehicle collisions, uninsured and underinsured motorist claims,

premises liability, catastrophic injury, and wrongful death.

His practice emphasizes claims evaluation, insurance carrier accountability, and litigation in California courts when fair resolution cannot be achieved. |